Writing about your firsthand encounters in the natural world and having the opportunity to share what delights you with your readers is hugely rewarding. But if you really want to your readers to experience what you see, hear, feel, smell, touch or even taste, as if they are standing next to you, then, if your memory is anything like mine, you probably need to find a way to capture the compelling details as soon as possible after you experience them. Finding your own approach to field research will help you do that.

At the outset of field research I sometimes have a specific question in mind, for example: ‘What birds are in St Paul’s Cathedral Gardens?’ On other occasions, I’m just bumbling along with no particular question other than ‘What’s out here today?” In both cases, I’m open to being distracted by something or someone unexpected.

Some writers favour just pen and paper for making field research notes , but that’s never worked for me. Whether I’m on planned research expedition or just out and about getting on with life, I record descriptive notes on my phone or a digital voice recorder, augmented with phone pics and soundscape recordings.

Some of the my most valuable field notes are the conversations I have with random strangers about nature, often people who stop to ask what I’m looking at. I don’t try and record these conversations at the time, but I do my best to record them accurately immediately afterwards.

My field research ‘notes’ are often extensive. I try to be methodical with noting details about the location, weather, and all of the species I see, as I don’t want to come home and then realise I’ve forgotten things. And I’ve never regretted having many more notes than I could possibly use in the piece of writing I’m working on. What I don’t use immediately can sometimes be useful for a different writing project. With that in mind, I do take time to file my recordings and photos carefully, so that I can return to find what I’m looking for.

Opportunities for getting entirely experience-based nature writing published beyond in your nature diary blogs do exist but are limited. You’ll have considerably more potential outlets for your short-form nature writing if you can deftly combine firsthand experience with additional information. If you’re writing about a particular organism you’ve found or a landscape you’re looking at, as well as describing it for your readers, you could perhaps tell them something about it’s cultural significance, geography, biology or ecology. Then you’re giving the reader something extra.

Desk-based research can be valuable as long as you go about it with a few important considerations. If you’re planning to include general information, then make sure your sources are credible. Use natural history information curated by respected nature organisations rather than relying on AI summaries. And while most nature writing doesn’t need academic-style references, it’s a good idea to keep a list yourself of the information sources and websites you’ve drawn on for each piece you write.

If you’re after scientific findings, then it couldn’t be easier to find online scientific research reports to support your creative nature writing. The difficulty could be sorting through numerous papers on the topic.I’d recommend looking for the most up-to-date research papers in each case and those in peer-reviewed journals. It’s always worth trying to contact the lead author to see if they’ll give you a good quote to supplement the research findings and that also gives you the opportunity to check you’ve understood any research conclusions.

If you do decide to interview scientists or other experts, make sure you’ve prepared really well so you make the most of the time you have with them. Some of what they tell you can be used as information, with the addition of one or two of their most pertinent quotes. The example below is an extract from a feature on the Kittiwakes which nest in the centre of Newcastle in which a quote from an expert and a research finding are integrated into an account of walk around the city centre.

“Despite some very noisy sandblasting where the north side of the bridge is currently being repaired, there are at least two Kittiwakes already on nests. Based on Dan’s experiences with the Tyne birds over some decades, he believes that many prefer to come back to the nest they used the year before (or close beside it) and reconnect with their partners there. “If the mate doesn’t turn up, they may find another one”, he tells me, “and divorce isn’t unknown.” Zoologists at University of Durham found that each year a number of birds take a new mate even though the previous mate is still alive and present in the colony.”

I always make sure that any scientists I talk to or experts I quote have the opportunity to comment on the draft feature before it is submitted to the editor. I want them to be totally happy with how I’ve portrayed them and their work.

As well as making use of already published information, you could collect your own information directly. Contributing to citizen science projects is one way of doing that and you could write about the data you collect and submit. Another approach that I make occasional use of in feature writing is asking on social media for experiences or opinions on topics. After checking I have the quoter’s permission, I might then either integrate their quote into the main body of the piece, or include a number of quotes in a separate list. On several occasions I’ve even conducted online surveys which have produced fantastic material. The example below is an extract from a feature about dogs and birdwatching.

“The 82 responses to a non-random survey I devise for birdwatchers – it wouldn’t impress a statistician – are interesting if not unexpected on views of dogs in nature reserves. Among the 26 dog-owning birdwatchers who responded, it seems that the more frequently you birdwatch, the less likely you are to think taking your dog with you to a reserve is a good idea. And if you’ve seen wild birds being disturbed by dogs, you were twice as likely to be negative about dogs in nature reserves, compared with respondents who said they hadn’t.”

The challenge for weaving into your nature writing the information from any of the above sources is making sure there isn’t an abrupt change in tone, for example from a creative description to a more formal-sounding bit of information. In the following example, the first four sentences are descriptive or contemplation. The last sentence is sourced information, but deliberately written in a similarly playful tone, and linked to the earlier part of the piece with a question.

“There’s a sprite in the garden! A peripheral blur on the wall-breaking valerian, pinging from pink to pink. This humming, hawking summer visitor – so full of energy and verve – punctures my doldrums. Most years, the doldrums and these hawkmoths return, just as the days start to cool and shorten. But from where has this exotic beauty come? It’s likely an adventurer from the parched Med region, zipping north in search of the last of the summer’s nectar.“

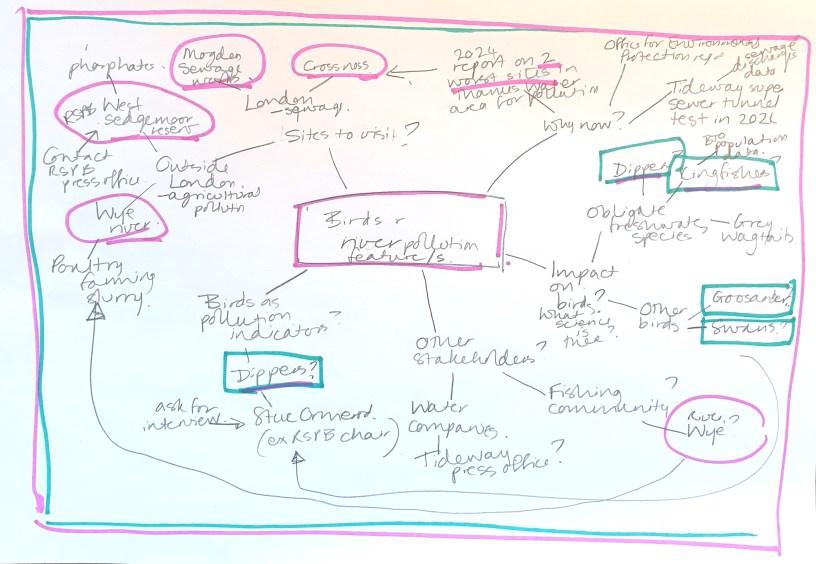

The example below is an extract from a feature I wrote about the impact of water pollution on birds. Here I’ve introduced some key facts into part of an account of a bird watching trip in London. My aim was to directly link the information about sewage release to what I was seeing.

“Around a kilometre further east along the Thames path is a second outfall, this time where treated sewage from the sewage works is bubbling up vigorously from a pipe under the shallow water. If you needed convincing that the release of treated sewage at Teddington will have an impact on bird- and other wildlife then this would be a good place to visit. Here I find another concentration of even more diverse birds – Shelduck, Shoveller, Teal, Wigeon, Gadwall, Redshank, Common Sandpiper, Black-tailed Godwit, Black-headed Gulls, Cormorants and, of course, Moorhens – attracted to the treated outflow. This treated water should in theory be meeting the Environment Agency’s standards for nutrient levels and chemicals like ammonia, but apparently still has sufficiently elevated nutrients to benefit invertebrates and algae, which then attract fish and birds.”

Doing effective research will help strengthen the credibility and impact of your nature writing, and researching for nature writing can and should be as enjoyable and rewarding as the actual drafting. I’ve shared above what works for me but I expect you’ll develop your own effective approaches to field research and desk research. And I do hope you enjoy it.