[Please do add comments to let me know which bits of this ‘essaylet’ you found useful or otherwise.]

At the start of a series of writing workshops or the start of the academic year, I always delight in meeting a group of new nature writers. It’s a great opportunity for me to revisit some basic but fundamental questions. What is ‘nature’ in the context of nature writing? Who are the nature writers everyone should be familiar with? And what are some of the key issues in nature writing? The first discussions we have around these questions are ones we return to over and over during the course and taking part in those discussions seems to help new nature writers as they navigate their way through the genre.

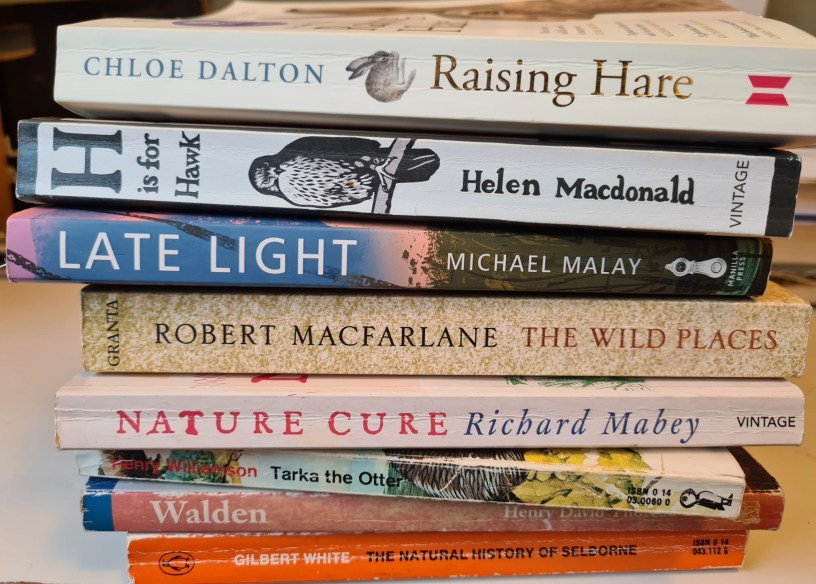

You could, of course, simply explore the history of nature writing through a chronological yomp through the ages from one significant text to the next… but, as well as being quite dull, that would also miss out something critical. For a writer, I’d argue that the most important, if not only, objective is to widen and deepen your understanding of past and present nature writing to benefit your own nature writing. With that in mind, it makes more sense to start with a contemporary text – in this case I’ve chosen Chloe Dalton’s 2024 much-awarded book Raising Hare – and to use this as a lens through which to view some milestone texts in nature-writing.

Reading is an essential element of taking a creative nature-writing course, but new writers can become overwhelmed by that sense that they can’t read whole books fast enough alongside finding time to practise their own writing. So it’s often at this point that I encourage them to identify some core books to read, and then offer ‘hacks’ for how to widen your knowledge of trends and issues in the genre. I’ll sometimes use a diagram like the one below.

Working clockwise from the top of the diagram, bookshop managers will have put a lot of thought into which books justify being on display, so it’s a good idea to regularly scan nature writing tables and shelves in bookshops, to give you an idea of the topics of new popular books, and which older books remain popular. Following the short-listing and discussions around nature-writing prizes also helps you clarify the direction of nature writing. Literary criticism essays explore key themes and issues in the genre. And, finally, studying book covers, reading book reviews and published extracts all help you gain a wider sense of the range of texts in creative nature-writing.

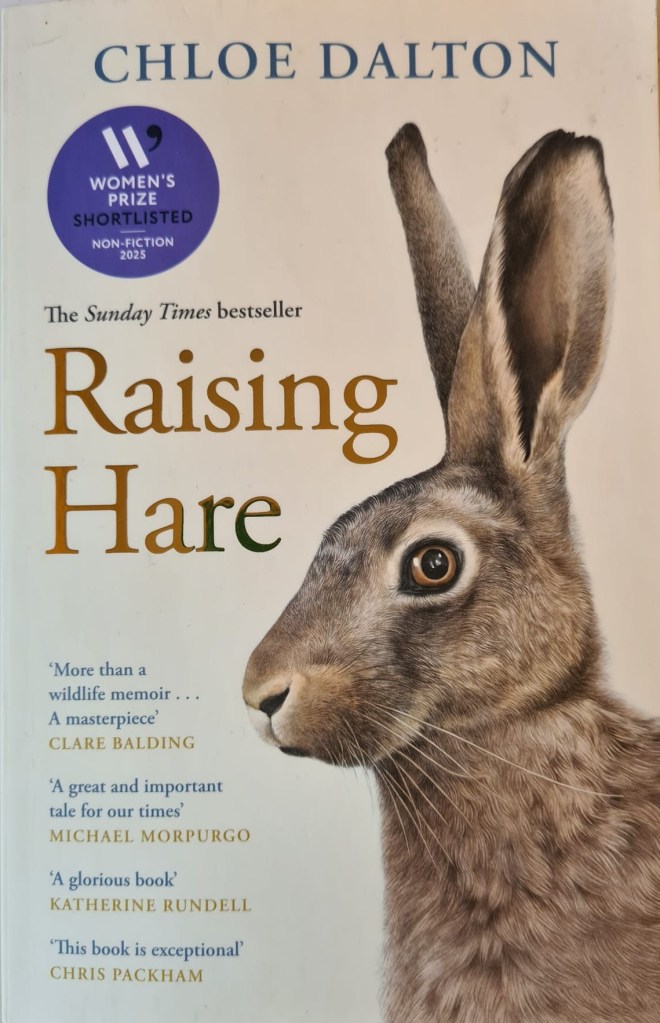

Let’s have a go analysing the cover of Raising Hare. Here’s the front of the book, which it might be useful to chunk up into a) the design and images, b) the endorsements, and c) the sticker.

It’s a bold design, dominated with an almost scientific illustration of a brown hare, far from the kind of illustration which might be used on a children’s book, for example. What does that tell us about the book? Is it, for example, suggesting that the author looks closely and unsentimentally at the subject?

The choice of front cover endorsers is interesting too. Clare Balding is best known as a TV presenter with an interest in walking, Michael Morpugo as a children’s author, Katherine Rundell as an academic and previous winner of the Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing, with Chris Packham as the only bona fide naturalist.

Raising Hare was both short-listed for the Women’s Prize for Non-fiction – as indicated on this cover – and went on to win the 2025 Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing. It’s a book which spans nature writing and general non-fiction.

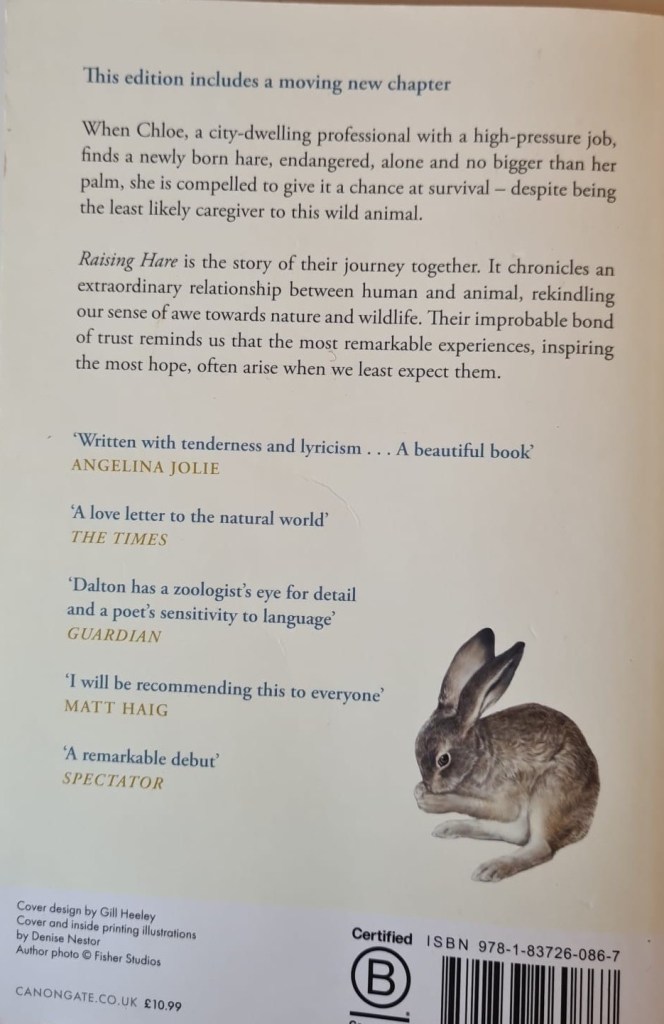

Turning to the rear cover, we begin to get an understanding of the book’s topic and ‘angle’ from the blurb – in a sentence, these could perhaps be summarised as ‘Professional woman in high-pressure job rears a newly-born hare, despite being a “least likely caregiver”, and this leads to an exploration of the relationship between humans and wildlife’. The reference to “least likely caregiver” is worth noting for future discussion.

Again the chosen endorsements are interesting, with a high-profile film actor, a couple of broadsheet newspapers and an author perhaps best known for fiction and non-fiction wellbeing books.

The illustration is a ‘cuter’ image of a hare than the one on the front cover. Perhaps this book isn’t going to be as unsentimental as you originally thought.

Raising Hare has been commended for Dalton’s for her detailed descriptions of the animals she encounters, for example in The Guardian “Dalton has a zoologist’s eye for detail and a poet’s sensitivity to language; she conjures the beauty, the allure and variation of the hare’s sounds, mouth, eyes and fur, which changes with the seasons and marks the passage of time.”

See this extract from page 45. “As the Earth’s winter palette gave way to the lush green growth of spring, the leveret’s colouring shifted. Its fur lost its dark chocolate hue, until its paws, flanks and chest were the colour of spilt cream, and only the fur on its back and ears still recalled its newborn pelt. The leveret’s eyes also began to change colour, from their original inky black. Hares aren’t born with the amber eyes they are known for. Over the course of a month, a pale outer ring developed round the black pupil, turning gradually into a striking, glowing iris.”

Detailed and almost scientifically accurate descriptions from observation is core to much compelling nature writing, and can be traced back to Gilbert White’s 1789 The Natural History of Selborne, arguably the first nature writing book. White was a parson naturalist who described the nature he found in his parish in Hampshire and asked questions about it in a series of letters to naturalist friends and acquaintances. In one letter, he describes a bird, which is the first accurate description of a sedge warbler in print. “My bird I describe thus: ‘It is a size less than the grasshopper-lark; the head, back, and coverts of the wings of a dusky brown, without those dark spots of the grasshopper-lark: over each eye is a milk-white stroke; the chin and throat are white, and the under parts of a yellowish white; the rump is tawny and the feathers of the tail sharp-pointed…” (p65 in Penguin Edition with an introduction by Richard Mabey.)

Convincing descriptions are hard to fake. After reading Dalton’s or White’s descriptions, you’re likely to be convinced they really did see and study those animals, but narrative non-fiction and memoir is rife with authenticity issues. Revelations about the ‘truth’ of Raynor Winn’s memoir The Salt Path, whether or not they were fair or valid, rocked the publishing world and probably caused a collective shudder among non-fiction writers. But perhaps the sophistication of the audience is being underestimated? Does the average reader accept that narrative non-fiction is often creative? How important is to you as a reader that the narrative happened precisely as written? Or do we have unreasonable expectations of the writer, that a memoir text emerges naturally and fully formed with only the slightest structuring and editing needed. The detailed chronology and descriptions in Raising Hare suggests Dalton was keeping a diary, and may have planned for this to be a book from the outset. If that was the case, would it affect how you view the book’s authenticity and how you value it?

Questions of authenticity in nature writing aren’t limited to whether the narrative happened exactly as written, but sometimes extending to whether the writer has been creative in the way they set up the premise and context. Raising Hare is presented as the story of one solitary woman and her relationship with a hare in a secluded cottage, with reference to Dalton’s contact with other people in asides rather than as part of the main narrative thread. The lone quest ‘into the wilderness’, or, in the case of Raising Hare, ‘into a relationship with the wild’, are common tropes in nature writing. US writer Henry David Thoreau wrote Walden (published 1854) while living alone for two years in a secluded cabin he’d built in the woods of Massachusetts. As Thoreau explained “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” (p63 in 1995 edition.)

While critics and conspiracy theorists have suggested without proof that Thoreau snuck home to his warm family home during the winter, it does seem possible that there cabin was less remote than the text suggests, with a neighbour within a mile and a community of homeless people living in the area. Does that matter? And does it matter if Dalton’s experience was less solitary and less surprising than the book suggests? You’ll remember that I asked you to note the expression “least likely caregiver” from the back cover, yet we read that her mother had a history of taking in and caring for injured animals, which perhaps makes her decision to care for the leveret considerably less surprising.

Most books described as nature writing are non-fiction, there are some examples of fiction writing which are bracketed in this genre, most notably Henry Williamson’s 1927 Tarka the Otter. Williamson spent four years researching the book to be able to present a convincing narrative without the presence of a narrator and making assumptions of human-like feelings, as shown in this passage. “When the moon gleamed out of the clouds in the east, pale and wasted as a bird in snow, the occasional whistles of the dog [otter] ceased. She did not care, for now she needed no comfort. She listened for another cry, feeble and mewing, and whenever she heard it, she rounded her neck to caress with her tongue a head smaller than one of her paws.” (p21)

The prologue of Raising Hare uses the same fictional approach, in contrast to the rest of the book. Dalton tells us what she imagines happened when the leveret was born. “One February night, the hare formed a nest in an overhang of tall grass at the edge of a field. There she gave birth silently under the moonlight to a leveret as dark as the night itself, save for a star-shaped white mark on its forehead. She licked it clean and then fed it, shielding it with her body until it had found use of its limbs, before nudging it anxiously out of its birthplace with her muzzle into a new hiding place within a dense tussock of dormant grass that created a snug tent around the little leveret…” (p2)

The relationship between humans and the natural world is key to Raising Hare. Like many other nature writing books it explores the emotional wellbeing benefits gained from closer contact with the natural world – the ‘nature fixed me’ trope – which could be seen as suggesting that the value of nature and the natural world is in its utility to humans. In Richard Mabey’s 2005 book Nature Cure he attempts to distance himself from this, although perhaps unconvincingly.“The idea of a ‘nature cure’ goes back as far as written history. If you expose yourself to the healing currents of the outdoors, the theory goes, your ill health will be rinsed away…. The idea was to submit to nature, to hope that it would ‘take you out of yourself… What healed me, I think, was almost the exact opposite process, a sense of being taken not out of myself, but back in, of nature entering me, firing up the wild bits of my imagination…” (p3)

Mabey seeks relief from depression and writers’ block by letting ‘nature enter him’, while ironically criticising other writers for there being too much “I” in their nature writing. Dalton references her workaholic tendencies and burnout and how the relationship with the female hare changed her. “She has taught me patience… She showed me a different life, and the richness of it. She made me perceive animals in a new light, in relation to her and to each other. I have learned to savour beautiful experiences while they last – however small and domestic they may be in scope. The sensation of wonder she ignited in me continues to burn, showing me that aspects of my life I thought were set in stone are in fact as malleable as wax, and may be shaped or reshaped. She did not change, I did. I have not tamed the hare, but in many ways the hare has stilled me.” p277

In 2008, Granta Magazine published an edition focused on what it called ‘The New Nature Writing’. The cover blurb suggested that, “…economic migration, overpopulation and climate change are transforming the natural world into something unfamiliar. As our conception and experience of nature changes, so too does the way we write about it…”

But was this just a clever label to launch an academic thesis or was there really a clear distinction to be made between ‘old’ and ‘new’ nature writing? The issues editor, Jason Cowley, had little time for nature writing written by naturalists, writing, “What I used to think of nature writing, or indeed the nature writer, I would picture a certain kind of man, and it would always be a man: bearded, badly dressed, ascetic, misanthropic. He would be alone on some blasted moor, with a notebook in one hand and binoculars in the other, seeking meaning and purpose through a larger communion with nature…” (p7) It did seem that writers described as New Nature Writers were as likely to be members of the literati as they were naturalists, scientists and/or conservationists. Robert Macfarlane, with his 2007 Wild Places and subsequent books, is one of the most successful writers in the genre, but many books in the nature writing genre are still written by writers who really know and understand their subject matter,

While it’s clearly not ‘New’ anymore, the positive impact of opening the genre to writers from a wider range of backgrounds had the benefit of increasing, for example, the number of nature writers of colour. Born in London to Indian parents from South Africa, journalist Jini Reddy’s 2020 book Wanderland was shortlisted for the Wainwright Nature Writing Prize despite the author seeming to have limited interest in the natural world. On the other hand, Michael Malay, Indonesian-born academic, won the Richard Jefferies and Wainwright prize for his 2023 book Late Light – The Secret Wonders of a Disappearing World and demonstrated a thirst for knowledge about British nature.

Like perhaps Macfarlane, Reddy and even Malay, Dalton seems to identify foremost as a writer rather than a naturalist, writing “… as someone who has made a living through words, she [the hare] has made me consider the dignity and pervasiveness of silence.” (p277)

Despite not winning the Wainwright Prize, Helen Macdonald’s 2014 book H is for Hawk went on to become of the best-selling books labelled nature-writing. Primarily about grief and the author’s relationship with a trained goshawk rather than nature, the book raises questions about the meaning of ‘nature’ and ‘wild’. Likewise, Raising Hare, despite the author’s protestations, is about a tame hare, a pet, which the author continues to feed for her own benefit. While she’s clearly aware of the conflict, at the point she could have returned the hare to the wild, dangers and all, she chooses not to. “I had raised the leveret with the goal of its return to the wild, and it had decided that it was ready. I had been spared the decision of when to open the gate and to expose it to the dangers in the landscape. It was always going to leave, as I was. All my plans were built on the idea of returning to work in London at the earliest opportunity, and now the way was cleared for that. This was surely the best possible outcome…” (p118)

Using Raising Hare as a starting point, we can explore the impact of key nature writing texts in both Britain and the US, and consider the ongoing issues and questions in contemporary nature writing. The titles highlighted in bold in this ‘essaylet’ are chosen as a shortlist of books I think every nature writer should have read to provide context for these genre questions as follows. How important is authenticity in memoir writing in particular in nature memoirs? What nature topics are ‘appropriate’ for nature writing (cultivated plants? pests? pets?) and when does an animal stop being wild? And a question I’m often asked, which is whether you need to know about nature to write about it.

As a reader who enjoys nature writing of the ‘creative nonfiction’ genre, I would say authenticity is very important. A really good nature writing book can elicit similar feelings to being in that nature without any of the discomforts (or in the case of Raising Hare, the anxiety and self-doubt).

I tend to prefer women nature writer’s partly because their work has been neglected or rejected in the past.

Favourites are Under the Sea-Wind by Rachel Carson, Findings, Sightlines and Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie, Refuge by Terry Tempest Williams, and Tove Jansson’s A Winter Book and Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty.

LikeLike