I freely admit it was a challenge for someone who is used to writing 1500-word features for my column in Bird Watching Magazine to make the shift to writing chapters of 5000 plus words when I started writing Wild Pavements. Looking for inspiration and expertise I turned to some of my favourite nature writing books of recent years and spent some time working out how the authors had constructed their chapters and woven different types of writing together.

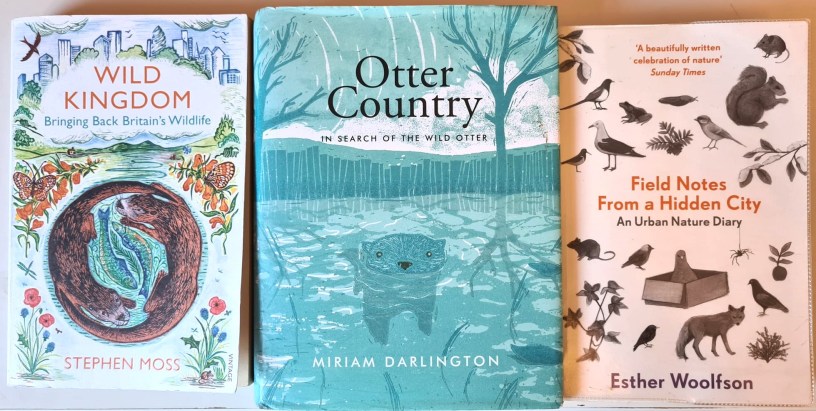

Take Wild Kingdom – Bringing Back Britain’s Wildlife – by my mentor, Stephen Moss, for example, and Chapter 6, ‘The Urban Jungle – Towns, Cities and Gardens’. The chapter is lengthy – 54 pages or approximately 13,000 words – and could almost stand alone as a short book. It’s written primarily in the past tense and, like the rest of the book, is made up of combination of first hand observation written in first-person present tense, historical information, and rhetorical sections where the author is talking to the reader also written in the present tense. The first part of the chapter is organised as follows:

- A paragraph quote (from Melissa Harrison’s, Clay)

- A 5-page section made up of Stephen’s observation of a peregrine hunting lapwings on Staines Reservoirs, a passage on the history of urban peregrines, reference to peregrines in other cities, and a section conclusion.

- A 6-page section opens with a ‘rhetorical’ passage including using the device of asking the reader to imagine the viewpoint of a bird flying over a city, and then follows with an information passage about urban nature, before a section conclusion.

- A 6-page section opens with information about the relationship city dwellers have with wildlife, followed by Stephen’s first-hand observation of the behaviour of a rural fox, contrasting it with an urban fox, then an information/rhetoric passage exploring attitudes towards urban foxes, before a section conclusion

- and so on before a 2-page chapter conclusion in which Stephen draws together the chapter themes.

Within each section the author deftly weaves different types of writing together. For example, focusing more closely on the first section, after a gripping first-person present tense account of seeing a peregrine hunting lapwings, he explains that this actually happened 30 years ago but the excitement of it “still lives with me”, which justifies the use of the present tense. Stephen then explains that the peregrine encounter happened by Staines reservoir in the western suburbs of London rather than the bird’s more ‘natural’ cliff and rock face habitats, and he continues with information about how peregrines have adapted to urban areas. Introducing how technology has helped our understanding of these predators, he then widens the view to the peregrines the reader can see in central Manchester, Norwich and elsewhere with the help of webcams and how this changes our lives.

As well as looking for ideas for how to structure chapters in Wild Kingdom, I paid close attention to how chapters were linked in another favourite book, Miriam Darlington’s Otter Country – In Search of the Wild Otter. In the chapter titled East, Miriam travels through Northumberland to Newcastle in search of otters. At the outset of the Newcastle section, she starts with crossing the Tyne bridge, and then moves to an information section about the city centre before returning to a first-person present account of meeting Jeanne, who has an otter which regularly visits her garden in suburban Newcastle. I really like the balance Miriam has between first-hand accounts and information, and the fine-grained way she weave these different types of writing together so seamlessly.

Other nature writing I admire – like Nicola Chester’s and Esther Woolfson’s, for example – offered alternative ways of structuring and linking chapters and I read and re-read carefully chapters carefully with a ‘writer’s eye’ to see how they did this.

The remainder of 2024 and beginning of 2025 were spent on writing research trips and writing the introduction and first 8 chapters, which amounted to half the first draft. I had submitted three chapters in my book proposal but these received a thorough revision too, to make sure they were structured and linked as effectively as possible. In the new year, I met online my commissioning editor at Flint Books, Claire, in spring 2025 so that she could give me verbal feedback on the first half. Despite my nervousness, thankfully her feedback made perfect sense and I took away notes of changes to make.

I had more or less finished drafting the remaining 8 chapters and epilogue by the end of March 2025, 11 months before P-day. It was at this point that I realised that my organisation of the references I’d used left much to be desired and I had to spend considerable time going through them one by one to check that they were accurate and attached to the right chapter. I finally finished this wearisome task – resolving to manage my references much more carefully in the future – and, after reading it aloud twice, I sent the first full draft of Wild Pavements over to the publisher to hit the end April 2025 deadline, 10 months before P-day.

Very interesting Amanda. There are frequent debates on social media about whether you can ‘teach’ creative writing, and while I’m sure some people have innate ‘writing gifts’ I’m equally certain we can all develop techniques to improve our craft. Our MMUC Creative Writing course unit ‘Reading as a Writer’ had the objective of analysing published work to identify what worked (or not), why and how. Exactly what you describe here. We can always learn, if we’re open to alternative ideas, approaches and structures.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for your comment Angi, and hope you are well.

LikeLike